Histories and Fairy Tales: Part 1

One of my favourite books as a child was James Burke’s Connections. The book (and indeed, the TV series which it accompanied), taught me that nothing is invented in perfect isolation: that previous and even parallel discoveries and inventions are paramount to the development of many modern day things. So, it must be noted that the history of photography is not a simple timeline: it is a messy weave of parallel threads knotted with notable events and competing vocabularies. It must also be separated out from the invention and development of the camera. That will be a story for Part II, or maybe even Part III.

But before I begin, another preliminary: I offer the following because, although it is a discredited theory, I am forever attracted to the perfect symmetry of the dusty old brass and cartridge paper science sensibility of Ernst Haekel‘s now thoroughly discredited Theory of Recapitulation. ‘Ontogeny,’ he stated, ‘recapitulates phylogeny.’ We know differently now. But I like to think that ontogeny (the study of the fertilised egg developing into the mature form) can still recapitulate phylogeny (the study of the development of the species) in the imagination, in poetry, in dreams, in images… The following history of photography is sort of mirrored in my own beginnings in the field, more of which later. In the meantime, making a linear tale of a vast historical and geographical panorama is difficult, so this is a potted history, or a story of connections and tangents. Believe the believable bits, forgive the recapitulations and discard the rest…

The Camera Obscura

In the dark and distant past, there were twinkling astrologers and robed scientists who, wielding brass oraries, astrolabes, calipers and crystal balls, experimented with alchemy and optics, and built darkened chambers, or camera obscura, to observe the properties of light and the projected images of the outside world falling, as if by magic, onto the inner walls of these chambers.

The images are magical. The science is beautiful. Light rays from the sun fall onto an object and are reflected in all directions. The white incident rays, coming directly from the sun, are composed of a wide spectrum of different wave lengths of light colours. The reflected rays, however, consist of the wave lengths of light which have not been absorbed by the surfaces of the objects from which they are reflected: it is these unabsorbed wavelengths of light that cause us to perceive colour in the surfaces from which they are reflected. If some of these reflected rays happen to travel through a small hole, or aperture, in say, the wooden shutters over a window, and fall onto the inner wall opposite, they are ‘interrupted’, and thus reflected again – enabling the eye to see them – and their colour information is disclosed. Thus, an image, often blurred but also often decipherable, appears on the wall. And because light travels in straight lines – a property which the camera obscura exposes and exploits – the projected image is always upside down.

Image of the New Royal Palace, Prague Castle (size aprox. 4 x 2 m) created on the attic wall by a hole in the tile roofing. Author: Gampe

Such projections can occur naturally in an ‘accidental’ camera obscura, as is evident in the attic of Prague Castle shown here, where a hole in a roof tile allows light rays reflected from the facade of a nearby building to be projected onto the attic wall; indeed, the principle has been known for thousands of years, the earliest known written account being Aristotle’s Problemata, in 350BC. Other early scholars such as Euclid, Chinese philosopher Mozi, and Arab philosopher Al-kindi also noted and explored the optical phenomenon, but the first clear account of the camera obscura is given by Arab scholar Alhazen in his Kitab al-Manazir or Book of Optics, dating from 1011 to 1021. Alhazen recommended the device for the safe observation of solar eclipses.

The Camera and Art

According to Matt Gatton, a multi-media artist in the States, these early philosophers and scientists were not the first to discover the principle. He proposes a paleo-camera theory whereby the depiction of animals in caves in Paleolithic times emerges after small piercings in the hide coverings of huts allowed light rays, and thus an image of whatever was outside, to project through into their interiors. He theorises that the plaquettes or large flat stones sometimes found in caves alongside the wall paintings, and upon which are scratched the animal drawings found on the walls, are highly significant: these plaquettes have had less impact on public consciousness, perhaps because they are not as spectacular as the paintings on the cave walls, but, Gatton theorises, they could be working drawings made in camera obscura hide huts and subsequently taken into caves to assist with the wall painting process. Should such a technique lessen the Paleolithic artists in our estimation? These are, after all, the paintings of which Picasso remarked: ‘We have learnt nothing!’

Except that he didn’t. Different stories have him exiting Lascaux, or Chauvet, or Altomira… And the vocabulary differs, but it’s a great fairy tale and demonstrates how myth overlays history. In the end, Matt Gatton’s theory can only ever be a theory, but its modus operandi of camera obscura assisted drawing is an idea not restricted to Gatton’s appealing but unprovable assertion: David Hockney proposed something similar in his book Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the lost secrets of the Old Masters, in which he describes making similar drawing experiments to Gatton, in comparing line marks made when capturing a person’s likeness from memory with those made when using a camera obscura. His case seems convincing, although now it is refuted robustly by David G. Stork et al in conference and in print (2011). I suppose that there are things we want to believe – like ontogenies mirroring phylogenies – because they are poetic or perfectly structured but, in the name of science, we must resist. The truth isn’t always a perfect narrative, it’s often a messy one. Nevertheless, there is something darkly attractive in the arcane secrets and contraptions of the alchemists and the old masters. Herein lies the evocative vocabulary of Fleur Adcock’s 1979 poem The Ex-Queen among the Astronomers…

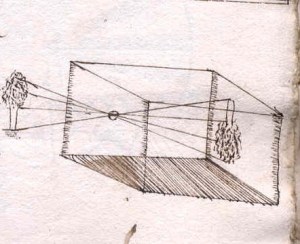

Seventeenth Century illustration of camera obscura from “Sketchbook on military art, including geometry, fortifications, artillery, mechanics, and pyrotechnics”. Source: Library of Congress

Whatever the truth of the Old Masters and their canvases and pin holes, other images do, however, demonstrate that later artists did set up camera obscura to capture distant vistas and buildings on paper or canvas. And some show that war and the military were, as ever, the driving forces of invention. And others, such as the sketches made by the great Canaletto given below, demonstrate unequivocally that resorting to the camera obscura was not the mark of a lesser artist: interpretation is still everything (in which case Matt Gratton’s theory does not diminish Paleolithic artists). In any case, the search for verisimilitude in art is perpetually unfinished, despite the solution offered in photography, and each era’s version of realism differs. As Descartes notes, “no image should completely liken the object it represents, for otherwise there could be no point of distinction between the object and its image” (cited in Fiorentini, 2006: 22).

Four drawings by Canaletto, representing Campo San Giovanni e Paolo in Venice, obtained with a Camera obscura. (Venice, Gallerie dell’Accademia)

I find this use of the camera obscura particularly interesting because it undercuts the perennial ‘Is Photography an Art?’ debate with evidence that some of the great artists used optical means to advance their work, and achieve a verisimilitude so very difficult, but not impossible, to achieve by aid of the eye alone: their achievements are underpinned, but not lessened, by a camera of sorts. Canaletto’s works are, after all, stunning in so many more ways than as accurate depictions of perspectives and spatial relationships. Funny that the desire for verisimilitude in art has driven the invention of the modern camera, and then when the camera is invented, art rejects it…

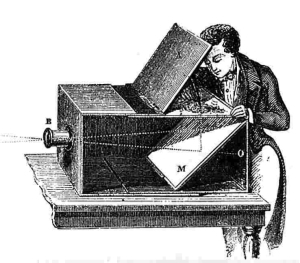

These same artists’s needs and desires led to the addition of lenses to the pinhole of the camera obscura for the better focusing of light falling onto the paper, and also the introduction of angled mirrors to the chamber to invert the projection so that artists no longer had to look at images upside down. At the same time, the chamber itself was shrinking to become a portable box for the serious artist or the amusement of ladies in parlours. This decrease in size, however, undoubtedly cost it some of its magic, for the camera obscura was a scientific instrument, a drawing tool and, certainly in its larger ‘room’ format, a magical entertainment: visitors to Edinburgh can still visit the Victorian camera obscura on the castle promontory and see live, moving images of the city below projected onto a dish in a darkened room. However uneasily pleased I think I am, the effect, when I saw it a few years ago, was magical, and I wasn’t alone: when the images first fell onto the table before us, the audience gasped. The mix of darkness and light is a potent one, and artists such as Chris Fraser and Abelardo Morell are still using the physics of the camera obscura to create beautiful and often ephemeral artworks made of light. But back in the late 1700s matters were progressing again. Artists were still dissatisfied with the new improved camera obscura: its lenses caused colour aberrations which made copying the colours of Nature difficult, nor did they find its focus sharp enough beyond the central area. Something else clearly needed to be invented.

These same artists’s needs and desires led to the addition of lenses to the pinhole of the camera obscura for the better focusing of light falling onto the paper, and also the introduction of angled mirrors to the chamber to invert the projection so that artists no longer had to look at images upside down. At the same time, the chamber itself was shrinking to become a portable box for the serious artist or the amusement of ladies in parlours. This decrease in size, however, undoubtedly cost it some of its magic, for the camera obscura was a scientific instrument, a drawing tool and, certainly in its larger ‘room’ format, a magical entertainment: visitors to Edinburgh can still visit the Victorian camera obscura on the castle promontory and see live, moving images of the city below projected onto a dish in a darkened room. However uneasily pleased I think I am, the effect, when I saw it a few years ago, was magical, and I wasn’t alone: when the images first fell onto the table before us, the audience gasped. The mix of darkness and light is a potent one, and artists such as Chris Fraser and Abelardo Morell are still using the physics of the camera obscura to create beautiful and often ephemeral artworks made of light. But back in the late 1700s matters were progressing again. Artists were still dissatisfied with the new improved camera obscura: its lenses caused colour aberrations which made copying the colours of Nature difficult, nor did they find its focus sharp enough beyond the central area. Something else clearly needed to be invented.

The Camera Lucida

In 1807, William Hyde Wollaston patented the camera lucida, a drawing tool similar to the camera obscura, but very much more portable for the artist in the field. Its optics had been described in 1611 by Johannes Kepler in his work on telescope refraction, Dioptrice seu demonstratio eorum quae visui & visibilibus propter Conspicilla ita pridem inventa accidunt (or Dioptrice for short), but had not been seriously exploited until Wollaston’s work. Erna Fiorentini makes a comprehensive comparative study of the two devices and I direct you there for more detail, but it’s safe to say artists were still not satisfied with either, for whatever the shortcomings of the camera obscura, the camera lucida had its own drawbacks not least of which was that it was notoriously difficult to use. It was William Henry Fox Talbot’s dissatisfaction with this aspect of it that led to him to wonder how its projected images might be fixed without the need for the artist to pencil in outlines by hand. The processes so far offered, after all, merely an artwork in outline only: the tones, textures and colours were still blank for the artist to fill in. Yet the image projected was tantalisingly life-like and rich.

James Burke’s comment that ‘Connections are made by accident’ is a simple truth. Perhaps the complex truth behind Fox Talbot’s connection to the invention of Photography is his desire to be better at art than he was. Inventions are, after all, sometimes about finding shortcuts. Perhaps this is at the heart of the suspicion with which art perceives photography: that the camera obscura, the camera lucida and the modern film or digital camera are somehow forms of cheating because they bypass the hours necessary to make a work by eye or from memory. How very far from the truth that turned out to be, what with all the messing around there was, especially for early pioneers, in the messy world of the chemical dark room.

Bibliography

Burke, J., (1978, 2007: reprint edn.) Connections, New York: Simon and Schuster.

Fiorentini, E., (2006) “Camera Obscura vs. Camera Lucida – Distinguishing Early Nineteenth Century Modes of Seeing” online: Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, http://www.mpiwg-berlin.mpg.de/Preprints/P307.PDF

Gatton, Matt. “First Light: Inside the Palaeolithic camera obscura” in Acts of Seeing: Artists, Scientists and the History of the Visual — a volume dedicated to Martin Kemp (Assimina Kaniari and Marina Wallace, eds.). London: Zidane, 2009.

Hockney, D., (2008, 2nd edn.) Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters, London: Thames and Hudson.

Stork, D.G., et al. “Did Early Renaissance Painters Trace Optically Produced Images? The Conclusions from Independent Scientists, Art Historians and Artists” in Stanco, F., S. Battiato & G. Gallo (eds.) (2011) Digital Imaging for Cultural Heritage Preservation: Analysis, Restoration, and Reconstruction of Ancient Artworks )(Digital Imaging and Computer Vision), Boca Raton: CRC Press.

Related articles

- Photographic Techniques (huinnngy.wordpress.com)

- InsideOut / UpsideDown (stellagrasso.wordpress.com)

- Exhibition: ‘Abelardo Morell: The Universe Next Door’ at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Getty Center, Los Angeles (artblart.com)

- Paleolithic Cinema (AncientCinema.atanomi.net)

- Reverse Engineering a Genius (Vanity Fair)